Predictably Misbehaving

Lecture 2: Reference-dependent Preferences

Joshua Foster at UW-Oshkosh

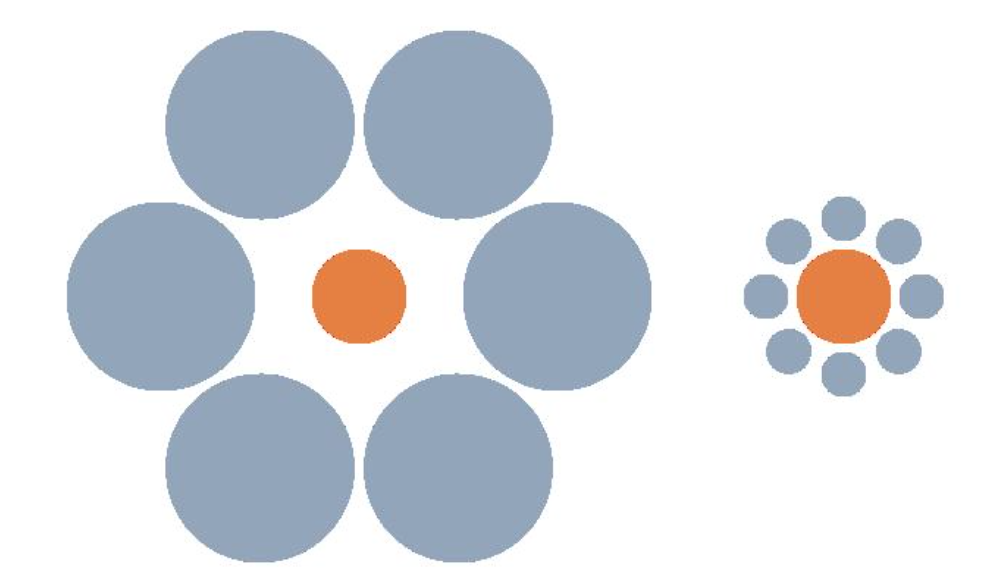

The Size-Contrast Illusion

The Ponzo Illusion

Comparative Perceptions

Our brains make relative comparisons, not absolute.

- Brightness, loudness, temperature...all relative comparisons.

- So are many of our experiences.

We find comparative judgments much easier to make.

- It's easy to tell which of two buckets of water is warmer.

- It's hard to tell their absolute temperature.

Today's Major Takeaway

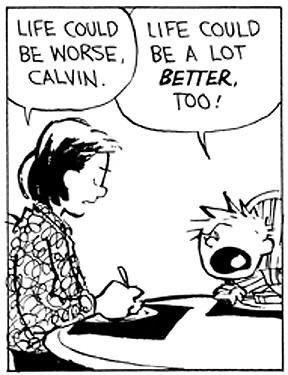

Evaluations of economic outcomes are heavily influenced by comparisons.

- One gets strong feelings comparing incomes.

- Say a friend makes $1000 more than you.

- It's hard to judge how much $1000 will help.

If absolute consumption is what made people happy...

- We should be happier than people 100 years ago.

- (e.g. electricity, indoor plumbing, entertainment)

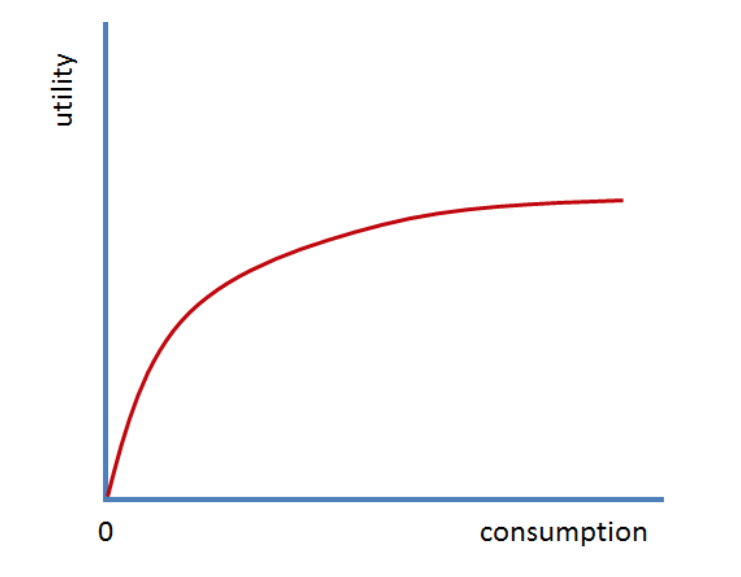

Traditional Economics

Traditional Utility

|

Traditional utility depends on absolute valuation.

|

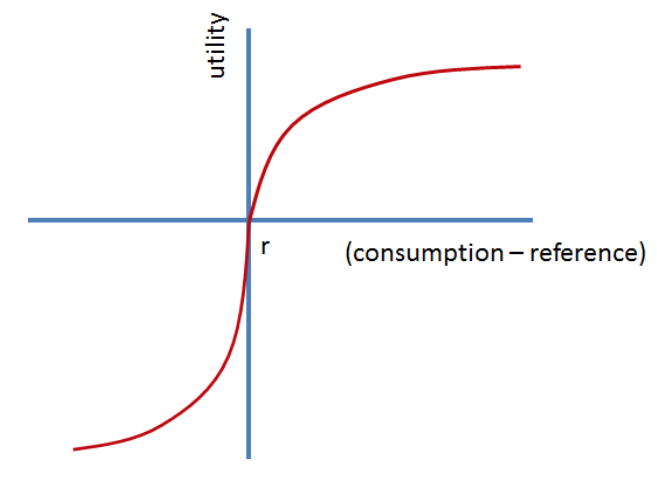

Modifications

Reference-dependent Utility

|

Reference-dependent (RD) utility depends on relative valuation.

|

Loss Aversion

For the consumption of something particular, people dislike losses relative to their reference point more than they like same-sized gains.

The inclusion of loss aversion is one of the most important properties of reference-dependent utility.

Loss Aversion

"How could we test for loss aversion?"

- Willingness to trade one's current position for an alternative.

- Preferences over risky gambles.

Compelling studies with evidence of loss aversion:

- Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1990, 1991)

- And many others...

Results: once a person comes to possess something they (almost) immediately value it more than before when they did not possess it.

Evidence of Loss Aversion

Endowment Effect

Endowing someone with a good almost instantaneously makes them value it more highly.

Experiments consistently find a major gap in prices:

- Selling prices tend to be $\sim 2\times$ the buying prices.

Testing the Endowment Effect

Experimental Procedure:

- Randomly give half of the subjects mugs.

- "Owners" and "non-owners" both examine them.

- Elicit buying and selling prices.

The Difficulty

Getting people to honestly state their value for a mug.

- The experiment must be incentive compatible.

- Otherwise, prices will not reflect their true valuations.

Becker-DeGroot-Marschak (BDM) Procedure

|

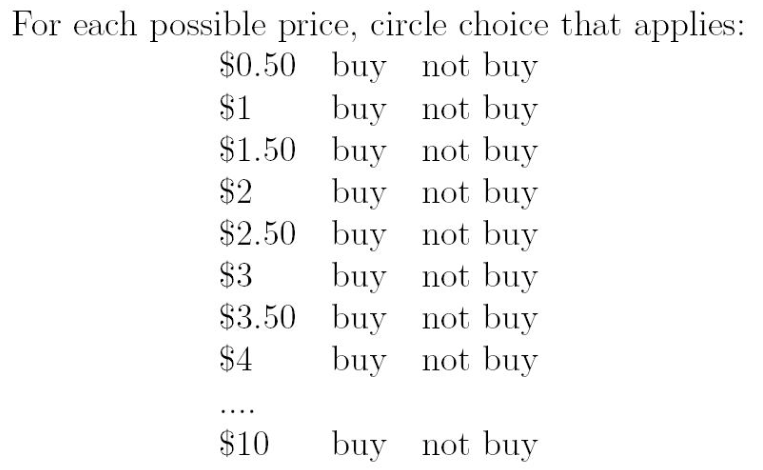

Each non-owner receives the following table to the left. Subjects are told a price will be selected randomly. |

Cannot to influence price, thus best to tell the truth.

Endowment Effect $=$ Reference-dependence $+$ Loss Aversion

| $\Delta$ in Mugs | $\Delta$ in Money | |

| Owners | 1 | 0 |

| Non-owners | 0 | 0 |

|

Selling a mug leads to

|

Buying a mug leads to

|

Loss aversion predicts that $x>y$. People need extra incentives to let go of what they already have.

What does traditional economis have to say?

There are potential measurement issues:

- Owners are slightly richer.

- Thus an income effect could explain this result.

Additional experiments were run to find out.

Meet the "Choosers"

Each non-owner receives one of the following tables.

Ownersvs.Choosers

At each $ amount, choose...the mug, or the money.

Endowment Effect Persists

| Owners | Non-owners | Choosers | ||

| 7.12 | $>$ | 2.87 | $\approx$ | 3.12 |

Major Takeaway: Low trade volume is due to owners' reluctance to part with their mug rather than buyers' unwillingness to part with their cash.