Predictably Misbehaving

Lecture 5: Choice Over Time (Again)

Joshua Foster at UW-Oshkosh

Multiple Selves Approach

Moe: Oh, boy! The deep fryer's here. Heheh, I got it used from the navy. You can flash-fry a buffalo in forty seconds.

Homer: Forty seconds?!? But I want it now!

Extreme assumptions of behavior over time

Naivete:

An individual who does not realize they will change their mind. That is, they assume their future self will follow through on their (current) preferred plan.

Sophistication:

An individual who understands perfectly that they will change their mind, and does the best given future self's anticipated behavior.

How could we tell whether someone is naive or sophisticated?

- The use of commitment devices indicates sophistication.

- Ulysses is (at least partly) sophisticated.

- Misprediction of future behavior indicates naivete.

- Teenage smokers who predict that they will not be smoking in five years have a slightly higher probability of smoking (74%) than those who predict they will be smoking (72%).

(BTW, non-issue under dynamic consistency.)

Naivete Vs. Sophistication

Ex: When to quit smoking

Naive decision-makers:

- Start at the beginning (i.e. first time step).

- Solve for the optimal plan at that time step.

- (Assuming future selves will follow the plan.)

- The person takes the first step in that plan.

- Go to the next period and repeat.

Ex: When to quit smoking

Sophisticated decision-makers:

- Start at the end (i.e. last time step).

- Solve for optimal action.

- (Assuming the person made it that far.)

- Go back to the previous period.

- Solve for the optimal action, taking into account what happens in the future.

- Go back to the previous period, and repeat.

Applications of Hyperbolic Discounting

Default Effects

Madrian and Shea (2001) QJE 401(k) Participation

- These plans are offered by many employers.

- Primary way to privately save for retirement.

- Employees often decide themselves:

- How much of their pay to allocate to the 401(k)

- How to invest their funds.

- This company offered a match (up to 6% of income):

- For every $1 an employee put in their 401(k)

- The company added 50 cents.

On April 1, 1998, the company changed their policy.

Before:

- Employees could participate after one year.

- Were not automatically enrolled.

- (Could enroll easily at any time.)

After:

- All employees were immediately eligible.

- And they were automatically enrolled.

- (Could unenroll easily at any time.)

The authors compare the choices of these groups:

- "Window" cohort: those hired in 1998 before April 1

- (Not automatically enrolled.)

- "New" cohort: those hired in 1998 after April 1

- (Automatically enrolled.)

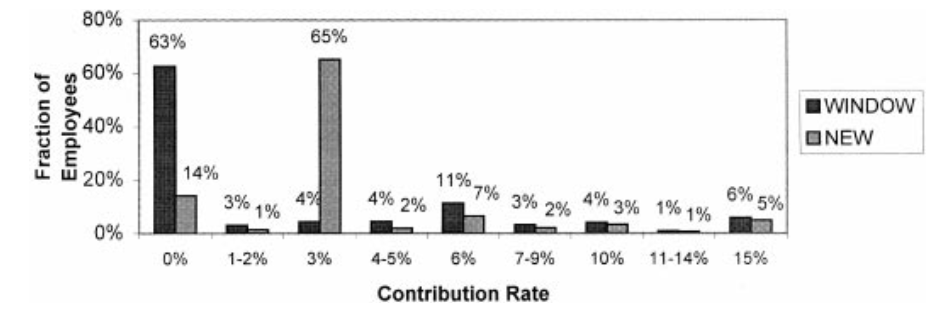

Results: Participation and Contribution Rates

Participation rates 3-15 months after being hired:

- 37% for the Window cohort

- 86% for the New cohort

The contribution rates were as follows:

The finding that defaults matter is one of the most important discoveries in applied microeconomics.

Getting a Grip on the Default Effect

This appears to be a big mistake by not participating.

- Offered a 50% return on up to 6% of your income.

Example: for an employee making $40,000.

- That's giving up a $1,200 gift from the company.

Even if it is not a mistake, why does the default matter so much?

- It only takes a phone call to change enrollment.

Would people not bother making a phone call for $1,200?

- If they are naive hyperbolic discounters, they might not.

- And as a result, defaults can be extremely important.

Making the Call:

"I'll do it tomorrow"

Costs and Benefits of Making the Call:

- Benefit: will get 5 per day (1,825 per year) extra for the next 30 years starting tomorrow.

- Cost: pain of the phone call today costs 30

Assume a naive hyperbolic discounter discounts the future at 80%.

When to make the call:

- Today: $-30+0.8\cdot[5\cdot 365\cdot 30] = 43770$

- Tomorrow: $0+0.8\cdot[-30+5\cdot 365\cdot 30 - 5] = 43772$

Hence, they put off making the phone call.

- If nothing changes they put off the phone call forever.

"I'll do it this week"

(Really, I will)

This prediction is extreme - and it's because the model is extreme.

- More reasonable prediction might be they delay for a long time.

Let's change the model:

- What would a sophisticate do?

- It's easy to argue they'd do it within a week.

- Waiting 8 days costs 40, valued at $0.8\cdot 40=32$

- Would rather pay the 30 cost today to avoid this outcome.

When exactly they make the call is a more difficult question.

Other Studies on Procrastination

Choi, et al. (2004) in NBER

- 401(k) contribution patterns generalize.

- Remarkably similar results across three industries.

Other Studies on Procrastination

Cronqvist and Thaler (2004) in AER:

- Looks at privatized retirement funds in Sweden.

- Heavily advertised by the government - 456 plans.

- Initially, 43% of participants chose the default.

- After 3 years, 92% of participants chose the default.

Other Studies on Procrastination

DellaVigna and Malmendier (2006) in AER:

- Study gym-goers' behavior at three US health clubs.

- Customers had two options for how to pay:

- Monthly fee of ~80 for unlimited use.

- Pay-per-visit fee of 10.

Most choose the monthly contract (89%)

- Those who do exercise 4.8 times/month (average)

- That's about 17 per visit.

Default Effect: go 2.31 months (average) without using membership before canceling.

It can be argued these findings are consistent with both extreme assumptions of hyperbolic discounting.

Naive hyperbolic discounters:

- Gym-goers prefer they exercise a lot in the future.

- Being naive, that's what they think they'll do.

- To save money on gym they buy the monthly membership.

- Short-run impatience kicks in, and they don't use the membership much.

Sophisticated hyperbolic discounters:

- Also prefer to exercise a lot in the future, but realize they won't.

- Use the monthly membership as a commitment tool.

- Willing to pay more (per-visit) if it helps get them to the gym.

Credit Card Teasers

Ausubel (1991) in AER

- Large experiment run by a credit card company.

- Mailed randomized credit card offers of three types:

- Standard: 6.9% rate for six months and then 16%.

- Teaser deal: 4.9% followed by 16%.

- Post-teaser deal: 6.9% followed by 14%.

- 21 months of data on take-ups and borrowing debt.

- Results:

- Teaser is 2.5 more successful than Post-teaser

- Given behavior, Post-teaser is a much better deal.

Credit Card Teasers

Explanations

Possible explanations from hyperbolic discounting:

- Naive borrowers believe they'll repay quickly.

- Hence the teaser interest rate is most important.

- Sophisticated borrowers don't want to use their credit cards much in the future.

- Hence choose a high interest rate to restrain future borrowing.