Behavioural

Economics

Session 18

Joshua

Foster

Agenda

- Case: New Zealand: Measuring What Matters.

- Closing thoughts: Reflecting on a semester of behavioural economics.

Reminder: all group project reports are due on Thursday before class (submit on Learn).

You must be present for both days of presentations.

What is Gross Domestic Product (GDP)?

If the goal is to maximize GDP, what types of policies should government implement?

What are the main driving factors behind New Zealand's decision to shift from a GDP-focused approach to a Wellbeing Budget?

"The purpose of government spending is to ensure citizens’ health and life satisfaction, and that — not wealth or economic growth — is the metric by which a country’s progress should be measured. GDP alone does not guarantee improvement to our living standards and does not take into account who benefits and who is left out."

--Jacinda Ardern

Prime Minister of New Zealand

"The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measure of national income."

--Simon Kuznets

Creator of GDP measure

What is the role of the Wellbeing Budget?

If the goal is to maximize citizen wellbeing, what types of policies should be implemented?

What is really at stake with a shift to a Wellbeing Budget?

If you are New Zealand's PM, what do you prioritize: GDP metrics or wellbeing metrics?

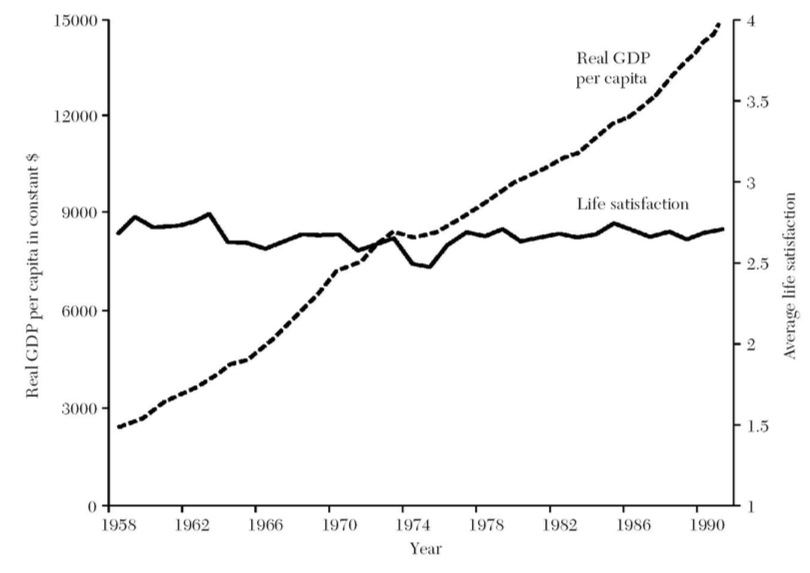

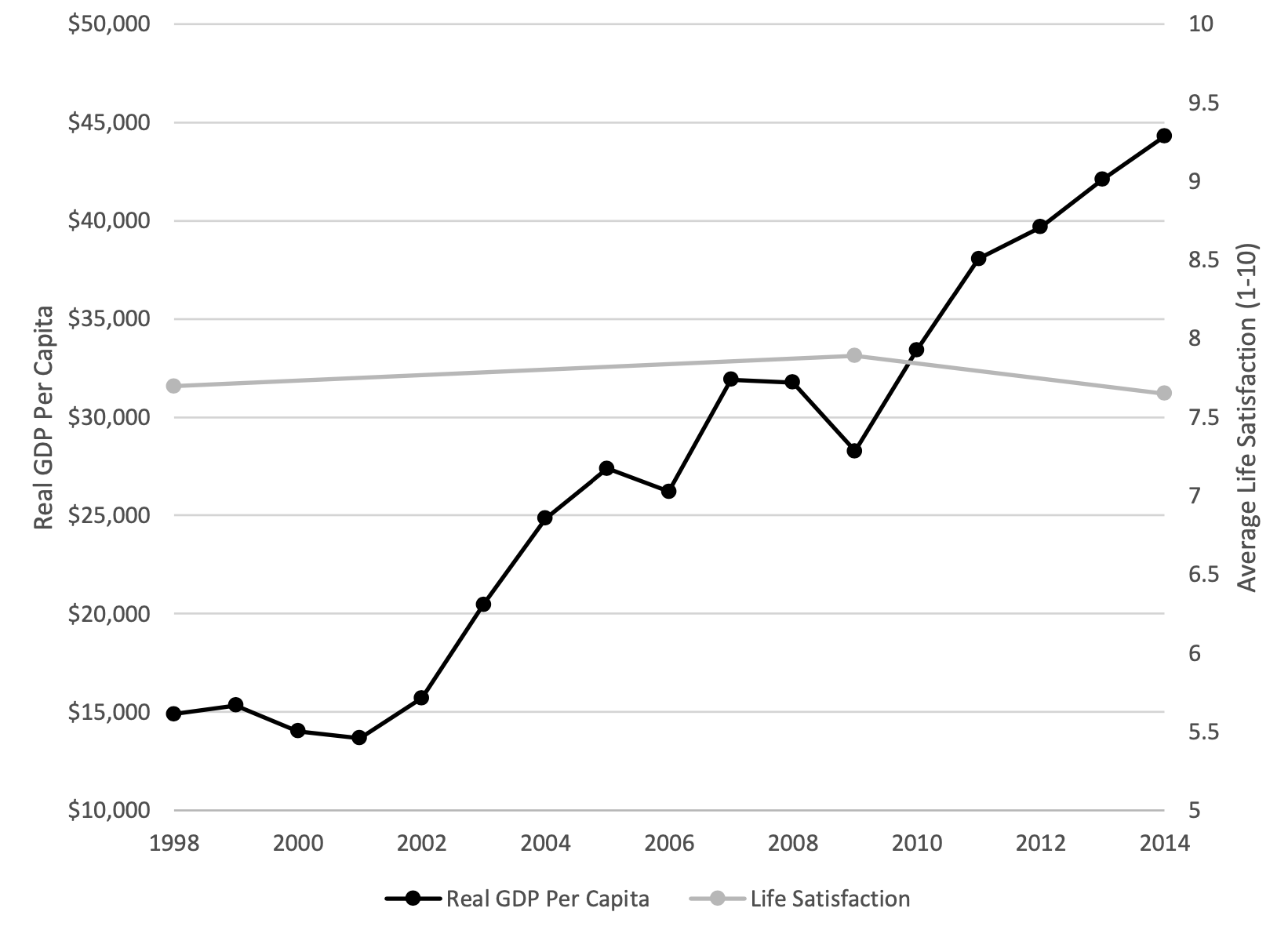

Easterlin Paradox.

Happiness varies by relative income, but not by absolute income.

- Being richer than your neighbor will make you happier than your neighbor.

- Being richer in five years will not make you happier than you are now.

Source: gapminder.org

Source: gapminder.org

Source: gapminder.org

Why does this happen?

Hedonic adaptation.

After a positive (or negative) event, and a corresponding increase (decrease) in utility, people return to a relatively stable baseline affect.

Brickman, Coates, and Janoff-Bulman (1978)

| Condition | General happiness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Past | Present | Futurea | |

| Study 1 | |||

| Winners | 3.77 | 4.00 | 4.20 |

| Controls | 3.32 | 3.82 | 4.14 |

| Victims | 4.41 | 2.96 | 4.32 |

Porsche Indicator P'6910 $\approx\$$225,000Fossil Chronograph $\approx\$$105

How does the Easterlin Paradox and hedonic adaptation complicate wellbeing metrics?

What do you prioritize in a Wellbeing Budget if happiness is determined by relative differences in income?

What are the potential long-term impacts of the Wellbeing Budget on New Zealand's citizens and economy?

What would determine its success or failure?

How might other nations learn from New Zealand's approach?

Key takeaways.

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is an insufficient measure of a nation's welfare and does not account for the distribution of benefits among citizens.

- New Zealand's shift to a Wellbeing Budget emphasizes the importance of citizen wellbeing over economic growth as measured by GDP.

- The Easterlin Paradox suggests that happiness is influenced by relative income rather than absolute income, complicating the use of economic metrics in policy decisions.

- Hedonic adaptation indicates that people return to a baseline level of happiness after positive or negative events, posing challenges for policies aimed at increasing long-term wellbeing.

In this class, you've had the opportunity to place yourself into many, distinct leadership roles.

- Business.

- Non-profit.

- Government.

In these roles we've explored several systematic errors and biases in judgment.

- Reference-dependent preferences.

- Short-term impatience.

- Subjective probabilities.

- Motivated reasoning.

- Bounded rationality.

- Warm glow giving.

- Social norms.

You now have an essential library of biases to guide you through a variety of problem spaces.

- Managerial hubris.

- Non-profit fundraising.

- Product positioning.

- PR management.

- Government policy.

- Market creation.

- Climate change.

And you have the tools to measure and enact positive change on behalf of the communities you serve.

- Experimentation.

- Nudges.

- Libertarian paternalism.

- Defaults.

- Commitment devices.